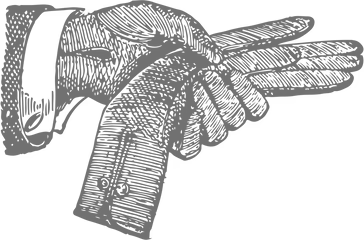

Carnutes, Statère à la lyre, 2nd-1st century BC

Gold - EF(40-45)

PLEASE NOTE: this collector's item is unique. We therefore cannot guarantee its availability over time and recommend that you do not delay too long in completing your purchase if you are interested.

Laureate Apollonian profile to the right. The wreath is made of inward-facing crescents. The top of the hair is made of flame-like locks.

On the cheek, a sort of tattoo in relief descending from the ear to the chin. The profile appears to be wearing a torque around the neck, the two pellet-shaped ends of it being clearly visible. At the base of the neck, a pearled line.

Biga to right, driven by an charioteer holding the reins in one hand and brandishing the other. Behind him, a four-spoked wheel. Below it, an upside-down lyre with the ends of the strings pelleted.

Superb specimen, with highly prominent relief, especially on the portrait. The flan has slightly cracked at the level of the horses' heads on the reverse when it was struck, so that the second head of the carriage is no longer visible, but the legs still make it clearly distinguishable. The charioteer is almost completely out of the flan, with only his arms and head visible. The lyre is clearly visible. On the reverse, the surface of the horse's chest is worn by circulation, which shows the very pronounced relief of the engravings. At almost 4.5mm thick, it is very rare to find flans with such engravings. Finally, this superb portrait is complete, with the nose clearly visible, as well as the locks of hair behind the head, although the wreath is slightly visible. This is the rarest variety of stater with a lyre and a tattooed cheek. The base of the neck is particularly interesting, as it clearly shows the circular shape of the circlet of a torque, and above all its pelleted ends, a detail that is not mentioned in the Délestrée and that seems almost never to be visible on the rare other specimens.

7.31 gr

Gold

Although nowadays gold enjoys a reputation as the king of precious metals, that was not always the case. For example, in Ancient Greece, Corinthian bronze was widely considered to be superior. However, over the course of time, it has established itself as the prince of money, even though it frequently vies with silver for the top spot as the standard.

Nevertheless, there are other metals which appear to be even more precious than this duo, take for example rhodium and platinum. That is certain. Yet, if the ore is not as available, how can money be produced in sufficient quantities? It is therefore a matter of striking a subtle balance between rarity and availability.

But it gets better: gold is not only virtually unreactive, whatever the storage conditions (and trouser pockets are hardly the most precious of storage cases), but also malleable (coins and engravers appreciate that).

It thus represents the ideal mix for striking coins without delay – and we were not going to let it slip away!

The chemical symbol for gold is Au, which derives from its Latin name aurum. Its origins are probably extraterrestrial, effectively stardust released following a violent collision between two neutron stars. Not merely precious, but equally poetic…

The first gold coins were minted by the kings of Lydia, probably between the 8th and 6th century BC. Whereas nowadays the only gold coins minted are investment coins (bullion coins) or part of limited-edition series aimed at collectors, that was not always the case. And gold circulated extensively from hand to hand and from era to era, from the ancient gold deposits of the River Pactolus to the early years of the 20th century.

As a precious metal, in the same way as silver, gold is used for minting coins with intrinsic value, which is to say the value of which is constituted by the metal from which they are made. Even so, nowadays, the value to the collector frequently far exceeds that of the metal itself...

It should be noted that gold, which is naturally very malleable, is frequently supplemented with small amounts of other metals to render it harder.

The millesimal fineness (or alloy) of a coin indicates the exact proportion (in parts per thousand) of gold included in the composition. We thus speak, for example, of 999‰ gold or 999 parts of gold per 1 part of other metals. This measure is important for investment coins such as bullion. In France, it was expressed in carats until 1995.

An “EF(40-45)” quality

As in numismatics it is important that the state of conservation of an item be carefully evaluated before it is offered to a discerning collector with a keen eye.

This initially obscure acronym comprising two words describing the state of conservation is explained clearly here:

Extremely Fine

This means – more prosaically – that the coin has circulated well from hand to hand and pocket to pocket but the impact on its wear remains limited: the coins retains much of its mint luster, sharp detailing and little sign of being circulated. Closer examination with the naked eye reveals minor scratches or nicks.